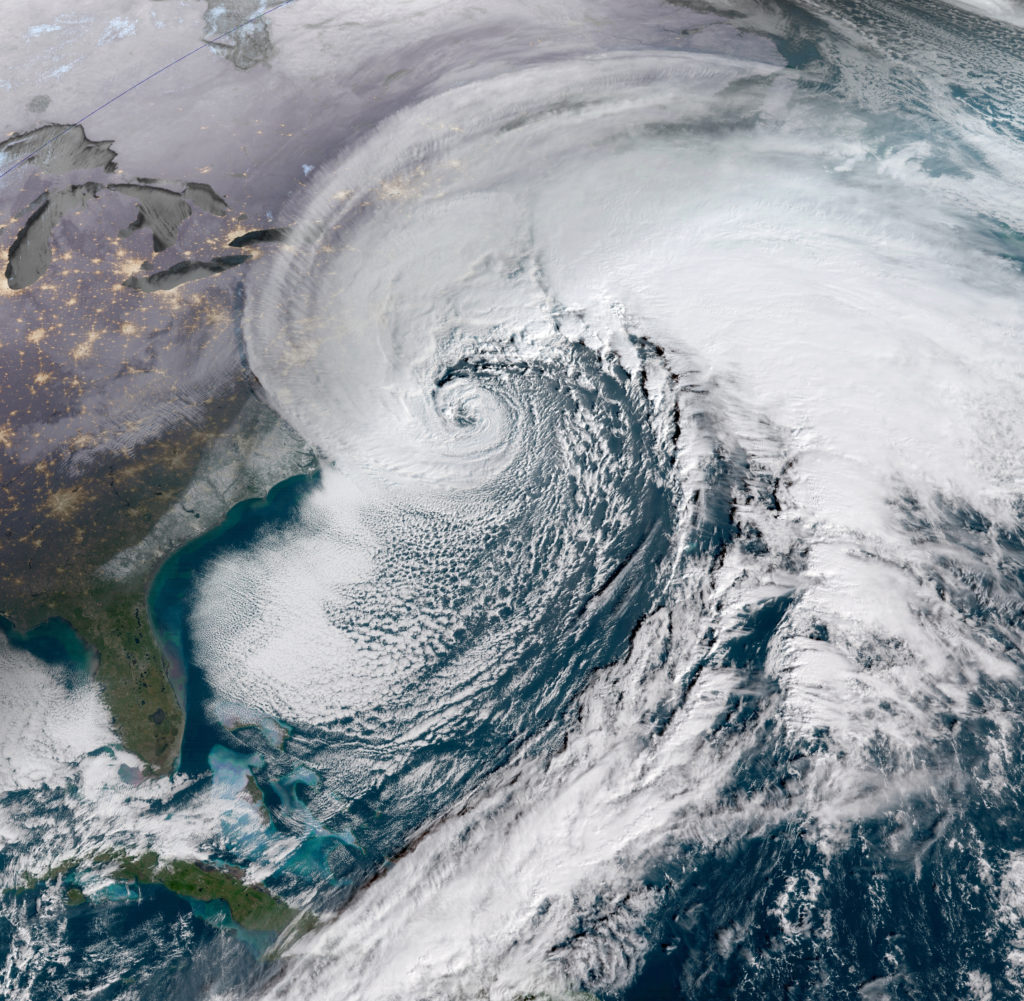

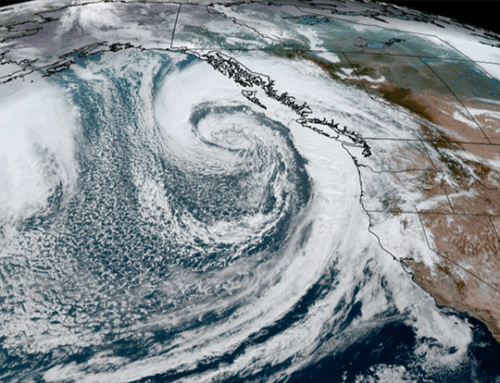

Meteorology is the study of the Earth’s atmosphere and the variations in temperature and moisture patterns that produce different weather conditions. Some of the major subjects of study are events like precipitation (rain and snow), thunderstorms, tornadoes, hurricanes, typhoons, and Nor’easters.

The outcome of meteorological events is felt in many ways. For example, a drought results in water shortages, crop damage, low river flow rates, and increased wildfire potential. In addition, these effects may lead to restricted river travel, saltwater infiltration in aquifers and coastal bays, stress on various plant and animal species, and even population shifts. The impact of weather on human activity has led to the development of the uncertain science of weather forecasting.

The word meteorology derives from the Greek word meteoron, which refers to any phenomenon in the sky. Aristotle’s Meteorologica (340 B.C.) concerned all phenomena above the ground. Astronomy, including the study of meteors, or “shooting stars,” later became a separate discipline. The science of meteorology was restricted eventually to the study of the atmosphere.

Key Takeaways

- Meteorology is the study of the Earth’s atmosphere, including temperature, moisture, pressure, and the processes that create weather.

- Modern meteorology relies on physics, computer modeling, satellites, and radar to observe and predict atmospheric behavior.

- Meteorology, climatology, and atmospheric sciences are related but distinct, with meteorology focusing on short-term weather and climatology on long-term patterns.

- Meteorologists use specialized tools and instruments—from thermometers and barometers to weather balloons and Doppler radar—to measure and analyze conditions.

- Meteorology plays a critical role in public safety and daily life, supporting aviation, marine navigation, agriculture, emergency response, and extreme weather forecasting.

Why Meteorology Matters

Meteorology matters because weather influences nearly every part of daily life from safety and transportation to agriculture and energy. Accurate forecasting helps protect communities from severe storms, guides pilots and mariners in planning safe routes, supports farmers in managing crops and water use, and improves the reliability of renewable energy systems. Meteorology also provides the foundation for understanding long-term climate patterns, shaping environmental policy, and helping people make informed decisions every day.

What Does a Meteorologist Do?

Meteorologists study the atmosphere to understand, interpret, and predict weather and climate patterns. Their work combines physics, environmental science, computer modeling, and direct observation to explain how atmospheric conditions develop and how they will change over time. Depending on their specialization, meteorologists contribute to a wide range of industries—far beyond daily weather forecasts.

Key responsibilities of meteorologists include:

- Observe and analyze atmospheric conditions

- Create short- and long-term weather forecasts

- Monitor severe weather and issue alerts

- Support industry-specific operations

- Conduct climate and atmospheric research

- Communicate weather insights to the public

Observe and analyze atmospheric conditions

Meteorologists collect data on temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind, and precipitation using instruments such as barometers, anemometers, satellites, radar systems, and weather balloons.

Create short- and long-term weather forecasts

Using computer models and real-time atmospheric data, meteorologists predict weather patterns ranging from local thunderstorms to large-scale systems such as hurricanes, cold fronts, and Nor’easters.

Monitor severe weather and issue alerts

Many meteorologists work in emergency management, helping governments, mariners, aviators, and communities prepare for extreme events such as tropical cyclones, tornadoes, and blizzards.

Support industry-specific operations

Specialized branches of meteorology—like aviation, agricultural, marine, and environmental meteorology—help industries make informed decisions. For example, marine meteorologists analyze ocean-atmosphere interactions that affect navigation, offshore operations, and coastal weather.

Conduct climate and atmospheric research

Research meteorologists study long-term atmospheric changes, energy transfer, cloud physics, and atmospheric chemistry. Their work contributes to climate models, environmental policy, and scientific understanding of Earth’s changing systems.

Communicate weather insights to the public

From broadcast meteorologists to scientific advisors, many professionals translate complex atmospheric data into clear and actionable information for everyday use.

Studying Meteorology Today

Modern meteorology focuses primarily on the typical weather patterns observed, including thunderstorms, tropical cyclones, fronts, hurricanes, typhoons, and various tropical water waves. Meteorology is usually considered to describe and study the physical basis for individual events. In contrast, climatology describes and studies the origin of atmospheric patterns observed over time.

The effort to understand the atmosphere draws on many fields of science and engineering. The study of atmospheric motions is called dynamic meteorology. It makes use of equations describing the behavior of a compressible fluid (air) on a rotating sphere (the Earth). One important complication in this study is the fact that the water in the atmosphere changes back and forth between solid, liquid, and gas in a very complex fashion. These changes greatly modify the equations used in dynamic meteorology.

Physical meteorology, or atmospheric physics, deals with several specialized areas of study. For example, the study of clouds and of the various forms of hydrometeors involves investigations into the behavior of water in the atmosphere. The study of radiative transfer is concerned with the fundamental source of energy that drives atmospheric processes, namely solar radiation, and the ways in which radiant energy in general is employed and dissipated in the atmosphere. Other specialized disciplines deal with phenomena involving light (atmospheric optics) and sound (atmospheric acoustics).

Some branches of meteorology are defined in terms of the size of the phenomena being studied. For example, micrometeorology is mainly the study of the small-scale interactions between the lowest level of the atmosphere and the surfaces with which it comes into contact. Mesoscale meteorology deals with phenomena of intermediate size — thunderstorms and mountain winds, for example. Synoptic meteorology is concerned with larger processes such as high- and low-pressure systems and their fronts, and so on up to the study of overall atmospheric circulation for time scales of a few days. Weather forecasting, the predictive aspect of meteorology, derives from these disciplines.

Meteorology vs. Atmospheric Sciences vs. Climatology

Though “Meteorology” and “Atmospheric Sciences” are often used interchangeably, they are not the same. Atmospheric sciences study the entirety of the Earth’s atmosphere, its processes, and the ways in which it interacts with the Earth’s water, landscape, and living beings.

“Atmospheric Sciences” can be considered an umbrella term for all things having to do with the atmosphere. Meteorology is just one sub-field of atmospheric science.

Climatology is another sub-field of atmospheric science and involves the specific study of atmospheric changes that define climates slowly over time. If meteorology is the study of weather, then climatology can be considered the study of weather over time. Climatology is an area of study quickly gaining popularity as climate change becomes a more pressing concern.

What Are the Different Branches of Meteorology?

What Are the Different Branches of Meteorology?

Besides meteorology and climatology, there are several other branches that focus on weather and climate.

- Barometry – The study of atmospheric pressure, how it is measured, and the ways in which it relates to weather and climate.

- Biometeorology – The study of how atmospheric conditions and weather patterns impact living conditions.

- Hydrometeorology – The study of how water and energy are transferred between the Earth’s surface and its atmosphere.

- Marine Meteorology – The study of overarching weather and climate systems and their effects on marine environments.

What Weather Instruments Do Meteorologists Use?

Modern technology has afforded professional and recreational meteorologists with sophisticated equipment that can detect regional and even global weather patterns. Additionally, modern radar, satellites, and computer modeling programs allow for long-term weather forecasts.

Some of the various weather instruments that meteorologists use include:

Temperature

Thermometers – The standard for measuring air, soil, and water temperatures.

Max & Min Thermometers – These record only the highest and lowest temperatures registered during a specific time period.

Resistance Temperature Detector (RTD) – Digitally determines air temperature based on the electrical resistance of a metal.

Atmospheric Pressure & Wind

Barometers – The standard for measuring atmospheric pressure.

Liquid Barometers – Contains an amount of mercury that changes as the atmospheric pressure increases or decreases.

Aneroid Barometers – These contain a fixed amount of sealed air within a flexible membrane. As the membrane expands or contracts with changes in air pressure, a needle points to the correct reading.

Wind Anemometer – The standard for measuring wind speed and direction.

Moisture

Hygrometer – The standard for measuring humidity, or the percentage of water vapor in the air. Other types include:

- Electrical Hygrometer

- Dew-Point Hygrometer

- Infrared Hygrometer

- Dew Cell

Psychrometer – Detects the difference in temperature between a dry thermometer bulb and a wet one to measure humidity.

Rain Gauges – The standard for measuring rainfall.

Snow Gauges – The standard for measuring snowfall.

Weather Balloons

Weather balloons measure humidity, air pressure, temperature, wind speed, and direction.

Weather balloons are launched at least twice a day from over a thousand sites around the world, where they rise to 20 miles above the earth and transmit information about atmospheric conditions back to meteorologists through radio waves.

Technological Tools

Ever since meteorological satellites began orbiting the earth and the invention of radar enabled these satellites to transmit information back down, long-term weather prediction on a global scale has become increasingly more accurate.

These high-tech tools include:

- Conventional Radar

- Doppler Radar

- Dual-Polarization Radar

- Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites

- Polar Operational Environmental Satellites

Other branches of meteorology focus on phenomena in specific locations, such as equatorial areas, the tropics, maritime regions, coastal areas, the poles, and mountains. The upper atmosphere is also studied separately. Other disciplines concentrate on taking observations with technologies, including radio, radar, and artificial satellite. Computer technology is applied extensively, including numerical weather prediction, interactive data analysis, and display systems.

The chemical behavior of the atmosphere, studied in atmospheric chemistry, has rapidly gained in importance due to inadvertent changes caused by humans in the molecular composition of the atmosphere. Changes in ozone (and the ozone layer) and carbon dioxide concentrations, and increased levels of acid rain, have gone beyond the status of local problems to become regional or global issues.

What Are Common Applications of Meteorology?

- Weather Forecasting

- Commodity Trading

- Aviation Meteorology

- Agricultural Meteorology

- Environmental Meteorology

- Hydrometeorology

- Synoptic Meteorology

- Maritime / Marine Meteorology

- Military Meteorology

- Nuclear Meteorology

- Renewable Energy

- Extreme Weather & Disaster Management

Meteorology Glossary

- Air Mass – A large volume of air that has consistent temperature and humidity characteristics.

- Atmospheric Pressure – The force exerted by the weight of air in the atmosphere; measured with a barometer.

- Barometer – An instrument used to measure atmospheric pressure and help predict changing weather conditions.

- Climatology – The study of long-term weather patterns and atmospheric trends over decades or centuries.

- Cold Front – The leading edge of a cold air mass moving into a warmer region, often producing storms or dramatic weather changes.

- Dew Point – The temperature at which air becomes saturated and water vapor begins to condense into dew or fog.

- Forecast Model – A computer-based simulation that uses atmospheric data to predict future weather conditions.

- Front – A boundary between two different air masses that often produces significant weather changes.

- Humidity – The amount of water vapor in the air; measured with a hygrometer.

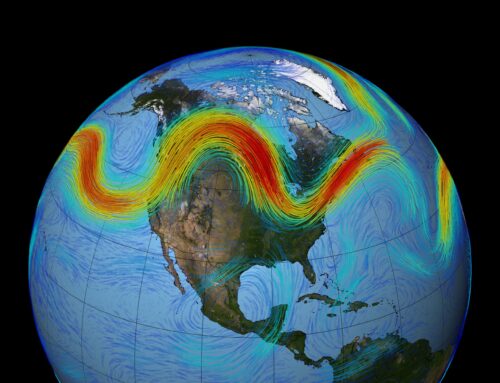

- Jet Stream – A fast-moving river of air high in the atmosphere that influences weather patterns and storm tracks.

- Low-Pressure System – An area where air rises, typically associated with clouds, storms, and unsettled weather.

- Mesoscale – Medium-sized weather phenomena, such as thunderstorms, sea breezes, or lake-effect snow.

- Meteorology – The scientific study of the atmosphere, weather processes, and atmospheric conditions.

- Psychrometer – A device that measures humidity using a wet-bulb and dry-bulb thermometer.

- Radar – Technology that uses radio waves to detect precipitation, storm movement, and weather intensity.

- Relative Humidity – A percentage describing how much moisture the air holds compared to the maximum it can hold at that temperature.

- Satellite Imagery – Weather observations collected from space to monitor storms, cloud cover, and global weather patterns.

- Synoptic Scale – Large-scale weather systems such as high-pressure systems, low-pressure systems, and frontal boundaries.

- Thermometer – A device used to measure temperature in the atmosphere, water, or soil.

- Warm Front – The leading edge of a warm air mass advancing into a cooler region, typically producing extended periods of cloudiness or precipitation.

- Weather Balloon – A balloon equipped with sensors that measure atmospheric temperature, humidity, pressure, and wind at different altitudes.

Ready to explore weather instruments that bring meteorology to life? Visit Maximum’s weather instrument collection to find high-quality tools for monitoring conditions right outside your door.

Meteorology FAQs

What is a simple definition of meteorology?

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth’s atmosphere, including the temperature, moisture, pressure, and motion that create weather. In simple terms, it explains how and why weather happens.

What is studied in meteorology?

Meteorology examines atmospheric conditions such as wind, humidity, temperature, air pressure, storms, and long-term weather patterns. It also explores how these elements interact to produce events like hurricanes, droughts, snowfall, and daily forecasts.

How is meteorology different from climatology?

Meteorology focuses on short-term atmospheric changes, what the weather will be today, tomorrow, or next week, while climatology studies long-term patterns that define regional and global climates over years or decades.

What tools do meteorologists use to study the atmosphere?

Meteorologists rely on instruments such as thermometers, barometers, hygrometers, rain and snow gauges, anemometers, weather balloons, radar systems, and satellites to observe and measure atmospheric conditions.

Why is meteorology important?

Meteorology helps protect lives and property by forecasting hazardous weather, supporting aviation and marine operations, guiding agricultural planning, and providing insights into climate-related risks and environmental changes.

My Comfortminder relative humidity doesn’t read accuratly.

60% vs. another electronic one reading 30% which is more reasonable given wintertime gas forced air (dry) heating. What do I do?

Please reach out to our technical support at 508-995-2200 and we’ll be happy to help you out!